By James Wilson

I am a graduate student in the department of entomology and I signed up for an independent class with Dr. Paul Marek. The idea has been that I can learn things about our collection and curating. You might imagine that insect collections are delicate things, and you would be right. Preserving, identifying, and organizing tens of thousands of insects is a huge job. Since Dr. Marek is now taking over the collection, we need to measure it to see what work has to be done to protect the collection and to make it more accessible. The collection is a big sleeping giant of a research tool. Each specimen has information for us. We collect a bug and record the date, location, and sometimes the habits of the insects, then place it and its label information into the collection. This doesn’t sound big, but when you multiply that information by the hundreds of thousands of specimens, you get an idea of just how much information is housed in these cabinets.

Collections conserve snapshots of the world around them so they can be used in the future, like a really well organized time capsule. When you make a collection you need to figure out how to save specimens, then identify and organize specimens so others can use it in the future. The future is here. Dr. Marek arrived at Virginia Tech this summer as a new hire and is now curating the collection. That means that he has come upon a huge time capsule.

Let’s open it!

One of the double cabinets filled with insect drawers (manufactured by prisoners in the Virginia prison system)

How do you measure boxes of bugs? Well, carefully.

Each cabinet has 20 or 40 of these drawers that are all organized taxonomically. Each drawer is also organized down to the family, subfamily, tribe, genus and species levels. Eventually you can go look for one species and be able to find it quickly in a box like this:

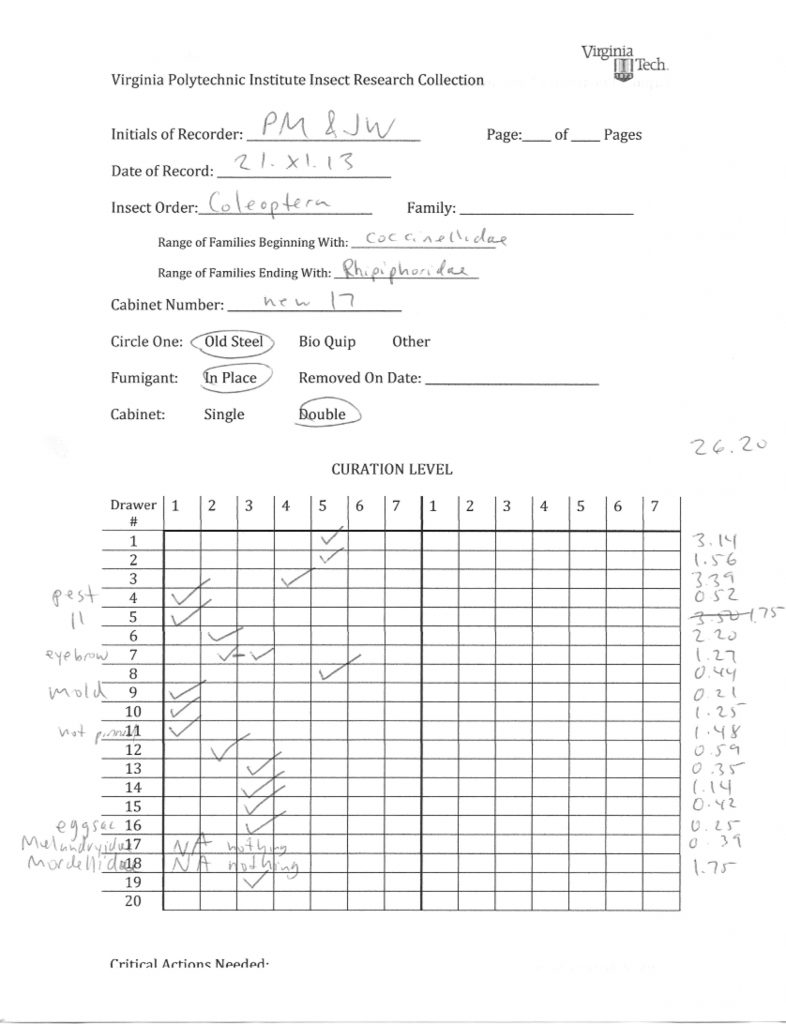

There are museums where scientists curate huge collections, while simultaneously trying to do research and manage their collections. To keep their jobs, they have to explain to other folks what they do, and why it’s important. Some collections require huge amounts of work while others can be dormant for long periods of time. To measure the status of their collections and to show just what needs to be done, scientists have come up with some measuring tools. First they focus on the conservation of the specimens, then the organization level, and eventually on how accessible is the information surrounding the specimens. This is where we started. We opened up a cabinet, pulled out some drawers and measured things up. We used the combination of a method described by McGinley at the Smithsonian in 1993 and by our neighbors at the North Carolina State Insect Collection. We looked at each drawer as a unit and in it assessed the status of the specimens. Were they all pinned, labeled, organized, and accessible for research? All of this allowed us to come up with a grade for each drawer. Take a look at what we came up with, and check back here later to see how we tied my field research in with this project.

Our review of the Lady Bird Beetles (Coccinellids) in the collection